Once upon a time adventure games ruled the roost. They were among the most popular, the most intelligent and the most critically-acclaimed games to grace the PC. While they never truly went away, it’s fair to say that they’re relegated to a niche interest.

One developer forcing his crowbar into that niche is Jan Mueller-Michaelis, the creative director of the German studio Daedalic Entertainment. Daedalic currently has over 100 staff working across a range of new adventure games. As we talked about their next release, the fantasy adventure The Night of the Rabbit, Mueller-Michaelis had a lot to say about what the genre can offer gamers, as well as the ways in which he believes this often unheralded area of old school gaming can wipe the floor with modern, high-budget titles.

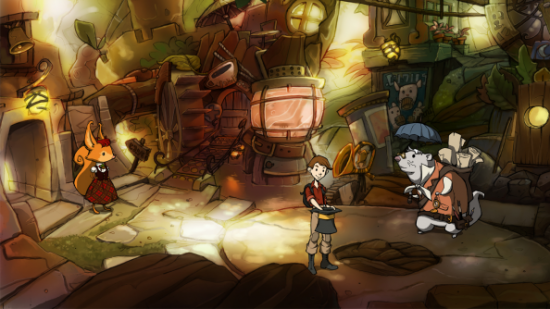

The Night of the Rabbit is not a fantasy game in the orcs-and-elves sense. Instead, it draws its inspiration from works such as Alice in Wonderland or the unusual and often alarmingly dark German fairy tales that many of us will have heard as children. The sort where youngsters are eaten and where curses are cast. “It’s about Jerry Hazelnut, a boy who dreams of becoming a magician, like we all had dreams of when we were young,” Mueller-Michaelis explains.“He finds a treasure chest that belonged to a real magician and this opens a gateway to a completely new world.” Jerry finds himself in the strange land of Mousewood.

Accompanying him on his journey is a rather cryptic companion, a giant rabbit known as the Marquis de Hoto, but a story that may at first seem to be riffing to Lewis Carroll’s already established tune gradually takes a series of ever darker twists and turns. At first, Jerry’s adventures are new and exciting, but something dark and sinister gradually begins to creep into the world of Mousewood, while his lupine friend might not be all that he seems. The Night of the Rabbit’s writer, Matt Kempke, thought he’d take a new angle on Carroll’s idea.

“Matt was was fascinated by the idea that Alice is just following the rabbit and the rabbit does not know about Alice, he has no plan,” says Mueller-Michaelis. “[Matt] asked himself the question, what if the rabbit had a plan, had watched Alice and had in fact chosen her to go into this world?” He adds that one of Kempke’s influences in this was a much more modern magician of sorts, famous for his fantastical jaunts: none other than the world-hopping Doctor Who.

As Jerry’s adventures unfold, the stakes gradually rise. The problems he must wrestle with and the puzzles he must solve become ever more urgent. “The more you spend time in Mousewood,” says Mueller-Michaelis, “the more the dark creeps into this world.” This is reflected in the sorts of problems you’ll find yourself solving, and Mueller-Michaelis says these puzzles will tell the story as much as any line of dialogue or exposition. In fact, they always should, he adds.

“It’s much easier to separate puzzles from the story itself and there are very many games that don’t get this mixture right,” he says, explaining that puzzles shouldn’t punctuate the plot or act as interruptions to the story, but must instead but instead be an integral part of it, since it’s your actions that shape the story and carry it forward. He also says that, even though developers have been making adventure games for several decades now, he thinks the genre is very young and still finding its way.

“The genre’s in its childhood as a medium for telling a story,” he continues. “We just have thirty years of history and we don’t know most of the possibilities that interactive media offers to tell a story, to mix it with the gameplay, to tell the story during the gameplay. It really feels like we’re visiting new land here, we are just staking our claims, going deeper into this new world and finding new ways to tell the story during the puzzles or via the puzzles.” I ask what we are learning, what makes for a cleverly-designed puzzle that supports rather than detracts from a game’s plot, and he has a particularly literary answer for me that explains how it’s all about relevance.

“In the theatre you have a very general principle of writing plays that’s called Chekhov’s Gun. He says that if you put a gun on the stage and you establish an object like that, you have to fire it in a later act, else it’s no use to bring it into the play. The audience will think about the gun subconsciously.” Of course, I think to myself, anyone playing an adventure game is going to want to use what they come across, else they’ll wonder why it’s there. “You should concentrate on what’s important for the story and leave the parts that distract from it: don’t include puzzles in the game that don’t tell the story.” At the same time, he adds the significance of any puzzle and the difficulty it poses should be relevant to how high the stakes have risen: “Make the objective equal to the problem [the adventurer] has to solve in this stage of the story, so that in fact the puzzle itself becomes kind of a metaphor for the conflict.”

It may be a strange thing to hear a developer say that they consider one of the PC’s earliest genres to still be in its infancy. Especially considering Daedalic make such old school, traditional adventure games, but Mueller-Michaelis doesn’t think he or any of his peers should be getting complacent about the titles that they make. Storytelling matters to him and, even after all this time, he believes the video games industry still has a long way to go and that adventure games can take the lead in this. As I ask him about the role of plot in games, particularly outside of adventure games, I find he has a lot to say on the subject.

“Adventure games have a quite unique place in the games landscape because they are themselves more literature than they are games. Almost every genre is able to tell a story, but not every game has to tell a story to be a good game,” he says. ”In adventure games the priorities are different. Here you have a story that features a game and not a game that features a story. The story is not laid out in cutscenes where before and after you have the gameplay, it’s during the gameplay.”

The very nature of adventure games, Mueller-Michaelis argues, means that plot is far more important to them, and far more relevant to a player’s actions and choices. Introducing a plot into, say, the latest high-profile first-person shooter can be much more difficult and can sometimes make for an unnecessary, clumsy and artificial addition, something that players will have no real connection to since they’re going to end up shooting things regardless of who says what to them. A plot should make you care, he tells me, it shouldn’t simply be a sideshow between the gunfights that are the real focus of the game.

“I think it’s kind of a misconception, in shooter games, to give them stories. I think they’re more about the gameplay and not about raising moral questions. Of course there are some shooters now that are including moral conflicts, but this would be the first thing to do if you wrote a story about war, for example, or about terrorism,” he says, adding that anyone writing for a first-person shooter may have their work cut out for them. “It’s really the hardest thing to do and I think that if you don’t try to comment on anything and don’t try to open a dialogue about the moral questions, you shouldn’t pretend to tell a story with your game,” he continues. “I think it would be better for such games to say ‘I’m telling a story or I’m just concentrating on the gameplay.’”

Otherwise, you find yourself in a middle ground with a very artificial compromise that adds nothing to the experience: ”It’s not much more than painting faces and characters on the box of a tabletop game. You have a game that’s just about tactics, or maybe has a luck component, and so that it sells better you draw some characters on the box so that you get some kind of emotional connection to it. I think that for most game genres, this is how story is used and that’s nothing I’m interested in.”

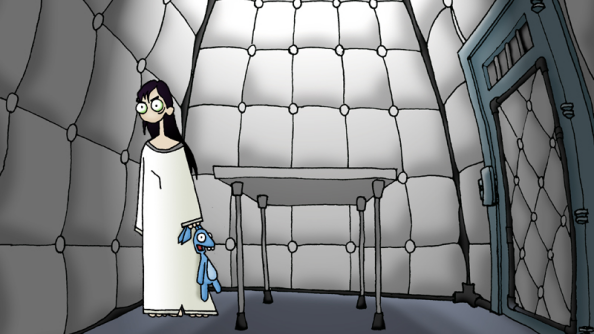

And when it comes to Daedalic’s own writing, Mueller-Michaelis says that the team put a lot of time and thought into both their plots and their puzzles. They want players to feel that they aren’t just being presented with good stories, but are also being forced to make difficult decisions. “Moral conflict stretches throughout our games,” he says. “Though they often look very cartoonish, like the Edna & Harvey series does, the content is quite mature, it’s very dark. Deep psychological conflicts are always the first things I start with when I write a story.” Edna & Harvey: The Breakout tells the story of a woman who wakes up in a padded cell with nothing but her stuffed toy for company. While it might appear lighthearted and frivolous at first, the plot takes a remarkably grave turn as the game progresses, following the internal conflict in poor Edna’s fractured mind.

“It’s about the psychological triangle that Sigmund Freud has laid out: the id, the ego and the superego, which always struggle against each other. Edna is this ego that is caught between the superego, represented by Doctor Marcel, the owner of the mental asylum, and her id, which is represented by Harvey.” The game, he says, is about being caught between these two powers “like between a rock and a hard place.”

It’s not the kind of game plot we usually find ourselves talking about, but Daedalic’s largely independent status means they have the freedom to craft stories like these, without worrying whether a publisher will sanction, for example, a female lead. “I think it’s a very special status that we have, that we are kind of an independent developer,” Mueller-Michaelis says. “I have the freedom to really write the story I want to, so I really don’t care about whether I’m allowed to include a female protagonist, or a black one. It doesn’t matter, I can just do it. It’s quite a luxury.” Daedalic’s writers can focus on writing the stories that they want to, he says, rather than the stories they’re told to.

“I can adopt the writer’s standpoint here and say that it’s always harder to tell an interesting story the more the publisher is taking control of the product,” he continues.” The more the publishers take control, the more narratives resemble each other, because they say ‘Oh, okay, now superheroes are in vogue, so everything that’s made should feature the same topic of superheroes.’ I’m very glad about this impulse that’s coming from the indie game scene. Nowadays it’s easier to make a game without the control of a publisher.”

Nevertheless, for all the maturity and diversity their storytelling can offer, adventure games still aren’t back in fashion and many of Daedalic’s releases go unheralded, especially outside of their native Germany. They’re busy completing the third of the Deponia trilogy, are developing a period piece called 1954: Alcatraz and have just begun work on Blackguards, an RPG that will be their second game based around the German roleplaying game The Dark Eye (their first, Chains of Satinav, is shown above). Mueller-Michaelis laments the waning of the genre, something he says is particularly tragic considering how much progress it had made.

“It struck me as very strange that adventure games [development] paused at the end of the last millenium,” he says. “It really struck me as totally wrong, because they’d built something up there. They were a new medium to tell a story interactively and I was so much into that. I loved them. The very last games like Full Throttle, the last King’s Quest, or the last Discworld game, they were really reaching a quality where you didn’t have to evolve the visuals any more and now you could concentrate on the story.”

And that’s very much where Daedalic want to carry the torch forward. Their take on adventure gaming is undeniably traditional, rooted in that late 90s era almost as if time had stopped, but they are nevertheless free to tell whatever stories they choose. While not all of of us are looking for something literary in our video games, and adventure games may not enjoy the reach or the exposure that they used to (indeed, some might say that era may be lost forever), I’m sure the chance to write with liberty and at length goes some way to making up for this.